Kathryn Bigelow is back, and this time, she’s dropped a slow-burning thriller that plays out in real time between the moment a hostile missile is detected and its projected impact over Chicago.

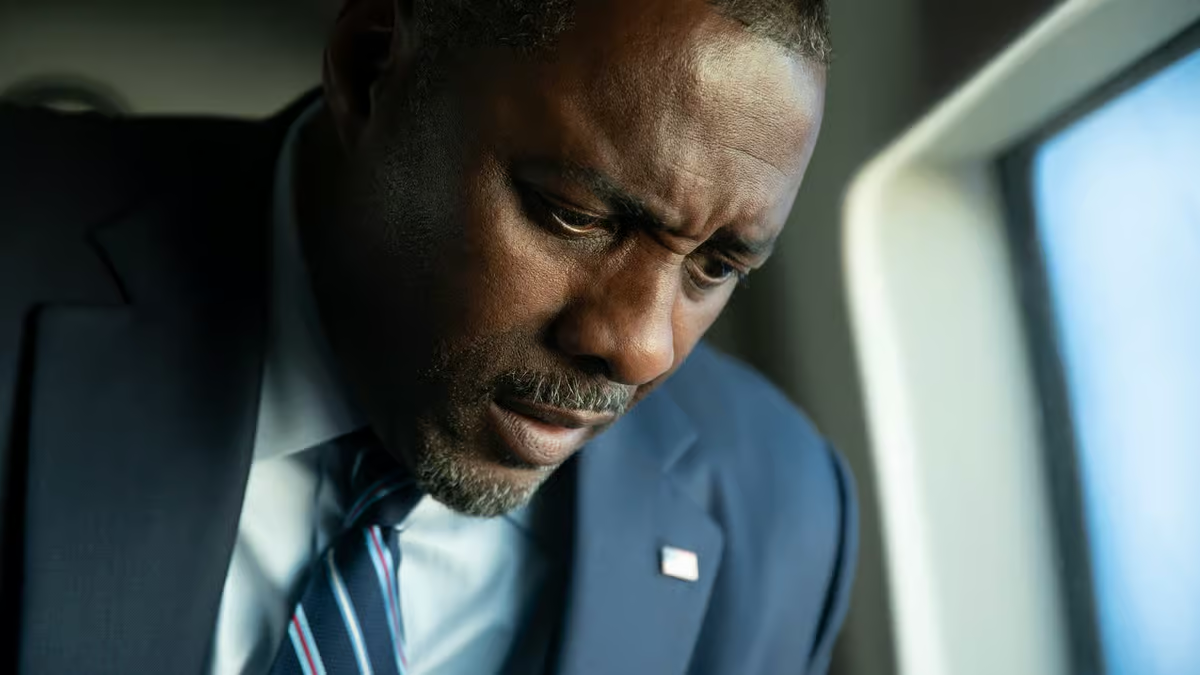

It’s intense, but not in the usual disaster-movie way. You don’t get explosions or massive crowds panicking. Instead, you watch people sitting in rooms all trying to stop something that might already be unstoppable. Idris Elba plays the president, and most of what he does involves giving orders, asking questions, and waiting.

That’s the point. What happens when we still have time to act (not much) but no one knows what to do with it?

From post-apocalypse to pre-apocalypse

In recent years, a cultural trend has emerged in popular media: the pre-apocalyptic narrative.

Unlike post-apocalyptic stories (which describe life “after” catastrophe), these stories shift focus from survival in a ruined world to the heavy burden of knowing what’s on the way. Instead of distant science fiction, they create tension in settings that feel close to home.

Lars von Trier’s Melancholia and Jeff Nichols’ Take Shelter helped kick off this trend. Melancholia follows two sisters in the final days before a planet hits Earth. Take Shelter is about a man who can’t tell if his visions of disaster are real or if he’s losing his mind. These stories care less about the event itself and more about how people handle the waiting. Don’t Look Up does something similar, using dark comedy to show how frustrating it is when nobody takes action, even with a comet headed straight for us.

House of Dynamite fits this approach. Pre-apocalyptic stories mirror current worries, like climate change, social tension, and financial instability. They connect with people because they feel close to reality.

One countdown, three perspectives

The movie tells the same eighteen minutes three times, from three different angles. The missile defense team in Alaska, analysts at the White House, and the president on Marine One. Each group is in its own bubble, under pressure, reacting in real time. No one sees the full picture.

The camera stays in tight spaces: military control rooms, video calls, mobile command centers. One scene shows a map tracking the missile and changing DEFCON levels on a massive screen. The design keeps attention on the process and the people making decisions, underlining the stress and confusion that build as time runs out.

Games that capture the same mood

Some video games have that same quiet dread you feel in A House of Dynamite. They ask: what does it feel like when the world starts coming apart?

- In Kentucky Route Zero, the characters are chasing an address that might not even be real. The story unfolds in a world shaped by economic collapse and quiet, systemic damage. It feels like everything is quietly breaking down.

- Pathologic builds a mood of creeping dread. You’re stuck in a town that’s falling apart, forced to make brutal choices that shape what happens next. And yes, it can all end in total ruin.

- This War of Mine flips the usual war-game setup. You’re not a soldier. You’re just trying to survive. Every day brings hard decisions, and every choice costs something. It shows war from a ground-level perspective, cold, slow, and personal.

- SOMA: a sci-fi story that uses its post-catastrophic setting to ask questions about identity and free will. While the world has already fallen, the core of the game revolves around what it means to be human.

The meaning behind the title

The title A House of Dynamite suggests that the places we think are safe might not be. A house usually means comfort, protection. Here, it’s a symbol of tension and hidden risk. Psychologist Russell Belk has described how people see their homes and belongings as part of their identity. William James, writing in the nineteenth century, said that a person includes everything they can call their own, including land and shelter.

In the film, that plays out through institutions and systems that are supposed to protect us but carry the seeds of their own failure. The decisions made inside those systems ripple out way beyond the walls. The danger isn’t just from the outside.

How it looks

House of Dynamite avoids typical disaster visuals and big effects. Instead of wide shots of damage, it uses steady, muted scenes with quiet tension: office rooms, empty streets, glowing screens. The lighting is plain. The camera movements are minimal. Most of the action plays out through faces, voices, and a countdown clock.

Cinematographer Barry Ackroyd uses handheld cameras and tight close-ups in bland rooms. It draws your attention to the decisions being made and the silence around them. The ordinariness of it all makes it more unsettling. These are world-ending stakes in the most boring-looking places.

Movies and games about the end of the world are usually reactions to what scares us in real life. During COVID, people flocked to these stories. Maybe for comfort, maybe to understand what was happening, maybe just to feel less alone in the worry.

Bigelow’s film shows how systems fall apart not just from outside attacks but from confusion and bureaucratic delays. People follow protocol, but the tools don’t always work. Communication breaks down. Nobody knows who fired the missile. It captures the fear of living inside systems that feel too big and broken to fix.

What would you do with eighteen minutes?

I’ve always loved post-apocalyptic movies and games. I joke that it’s practice for when it actually happens. Watching people survive in broken worlds makes me wonder how I’d handle it.

A House of Dynamite pulled me in the same way, even though it happens before the collapse.

It made me think: what would I do with eighteen minutes? Would I panic or stay calm? Call someone or just sit with it? That feeling, knowing something irreversible is coming but not when or how, stayed with me after the movie ended.

It left me wondering: is knowing about the end ahead of time a gift or a curse?