There is a concept floating around since the inception of storytelling called the “willing suspension of disbelief”. Basically it means that the audience gives the story a certain benefit of a doubt as far as realism is concerned. To quote the best time sink on the Internet, TvTropes, it boils down to “You can ask an audience to believe the impossible, but not the improbable”. That said, video games usually ask us to take at face value some pretty ridiculous things. Sometimes it’s fine, other times we end up writing articles about the gaminess of certain game mechanics.

Arbitrary stealth

Stealth in games is usually pretty weird. That weirdness is frequently a certain abstraction necessary to make the entire thing work. Take Hitman, for example, the entire franchise. On the surface the stealth makes sense: Agent 47 disguises himself in order to pass through certain areas undetected. Perfectly reasonable! The problem is his face.

With a face like that he’d be effectively invisible at some kind of Dracula-con, but Marrakesh? Japanese-staffed restaurant? Give me a break. For all his talent for hiding, Mr. Rieper looks like a bald vampire and sticks out like a sore thumb when disguised. And don’t even get me started on the serial number tattooed on his neck in a very visible place. A novelty, you’d think. Suspicious, every guard would think.

Of course Hitman isn’t the only one doing things like that. The idea of Solid Snake successfully hiding in plain sight under a cardboard box is so delightfully silly we accept it due to the Rule of Funny. Depending on your background you may consider it a regular natural 20 on a stealth check. Even the otherwise serious Phantom Pain didn’t shy away from some stealth silliness. And don’t even get me started on guard attention spans and eyesight, because we’d be here all day.

Arbitrary barriers

Some games like funneling us into a predetermined path. We get it. There are scripted explosion to be triggered, ghosts waiting patiently for us around the corner, and a very important comment from our companion about floating rocks. But could they be a little bit less blatant about this thing, maybe?

How often do games put us in a role of a hardened soldier able to take on two tanks and a full regiment of baddies? How often the tank-busting grenades don’t even dent a door we need to find a key for? Everyone who has ever played Pokémon knows the tree maliciously growing in the middle of a road we have no way of avoiding by taking a jump to the left, or a step to the right, not necessarily with your hands on your hips.

Yeah. At least Divinity: Original Sin decided that we can blast pretty much any dicrete object, doors and cdhests included.

Murder hobos

A term itself is derived from the tabletop roleplaying games, but applies very well to a disturbing number of video game characters, especially RPGs. The idea of “murder hobo” is pretty simple: your characters are typically homeless, endlessly going around doing odd jobs for random people, often involving killing some animals or more or less civilised beings. We are used to calling them “adventurers”, but are they, really?

Few games actually pay attention to it. Most recently The Witcher franchise kind of makes it a part of the reason why people dislike witchers. They come, they kill, they go, never once give a damn, at least in theory. Especially the classic Infinity Engine games and their descendants took wholeheartedly to the idea, letting you create a band of roving, nosy mercenaries with little concern for the NPCs around them. And nobody seems to care that by the end of their “adventure” these mercenaries are unstoppable killing machines with hundreds of kills under their belts, massive wealth, and have probably created numerous power vacuums the land will be recovering from for decades.

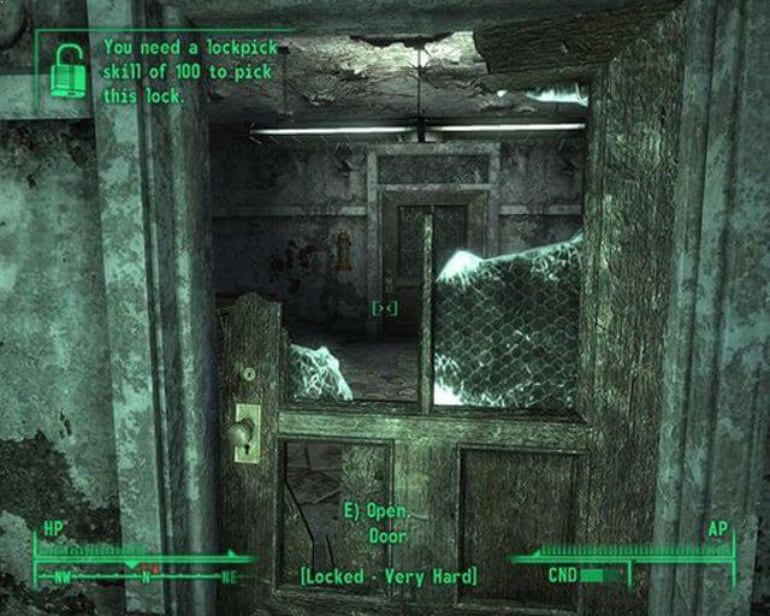

Snooping around

RPGs and action games have no respect for private property, at all. The slightest hint of a locked door or any sort of container and most gamers jump at the opportunity of finding out what’s inside.

Open-world games with some form of experience-based progression are the worst offenders. Every lock is a bit of EXP, after all, how could anyone ignore this? And there might be loot inside! How do you know a magic fork doesn’t hide in there? Your collection of useless loot won’t be complete without it! Never mind the owners of houses and lockers you rummage through, they’ll forget you existed when you walk outside. Not that it’s reserved only to fantasy settings. Each of the three Deus Ex protagonists (J.C. Denton, Alex D, Adam Jensen) has a weird tendency to read private emails from every terminal, for instance. Would it be considered trespassing or breaking-and-entering? Sure. Do games treat it as such? Hardly ever. Do player characters ever feel weird? You must be joking.

Iron stomach

There isn’t one creature with a better-adapted physiology than video game protagonists. Just think about it for a moment. After the events of a game the stomach, liver, and most likely kidneys of your character would be absolute wrecks. After a tough fight there’d be a deadly concentration of medkit contents in the character’s bloodstream, and nobody addresses the fact that there is still a dozen gunshot wounds all over the torso. Fantasy games are even harsher! We get that the potions are magical, but is it really a good idea to drink a health potion that has been oddly sitting in a tomb for the past 500 years? I mean, it clearly didn’t help the last guy. If you’re more interested in produce, then consider Skyrim, for example.

Just how many things can you cram into your stomach, you Dragonborn weirdo? Shaggy and Scooby Doo combined can’t eat that much, that fast!

On the other hand most video game characters can’t handle alcohol, really. A beer or two is enough to screw their aim so much it’s a miracle they aren’t walking into walls. Let’s have a moment of silence for Geralt in The Witcher 1, though, because booze struck him harder than any elixir. Either way, food or drink, I don’t even want to imagine the “morning after” these characters must suffer through on a regular basis.

Some kind of conclusion

To make things clear: we have no issue with any of these things. We’ve long since accepted the laws of the gaming world. We simply aimed to shine some light on the small and big absurdities most of us only rarely take a moment to think about while we’re playing. In the end, it’s the gameplay and stories that are important, not the abstractions games use to deliver them to us. Certainly, this text only barely scratches the surface, and even that only in broad strokes, to boot. Specific genres, often even individual franchises have their own quirks and departures from “realism” or “common sense”.

And it’s perfectly fine.