Poland in the 1980s wasn’t exactly Silicon Valley. Under communism, there were barely any computers, no game stores, and certainly no official game development scene. But nothing can stop true passion, and somehow, games still happened. People with access to Atari or Commodore machines traded software on cassette tapes. Hobbyists coded late at night, passed games between friends, or sold them at local electronics markets. This was DIY culture before anyone called it that way.

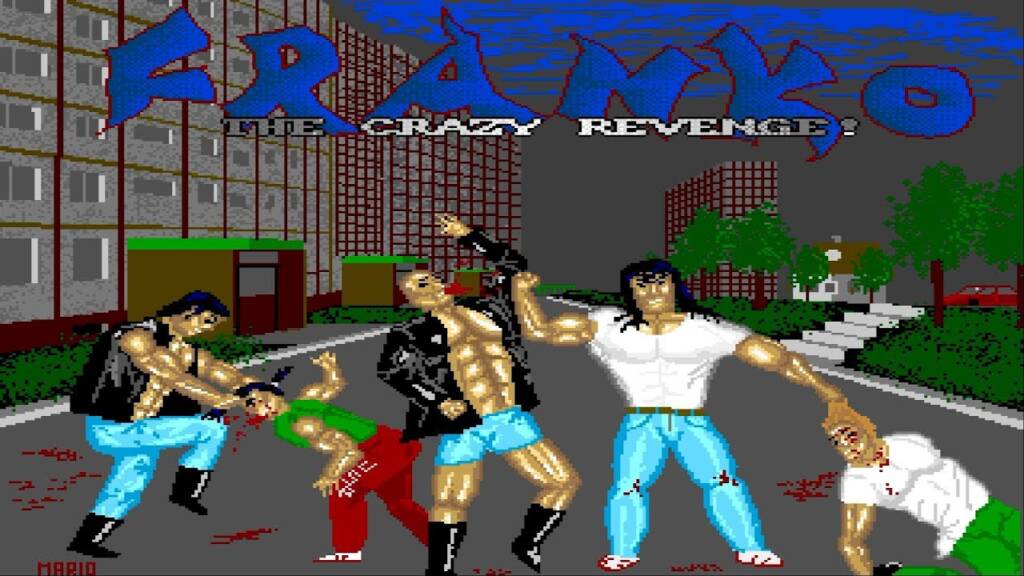

If you were a kid back then, you probably saw your first games in magazines like Bajtek or Top Secret. Maybe you typed code by hand from printed listings. Maybe you played Franko with friends, wondering why it was so violent.

Once the Iron Curtain fell in 1989, things moved fast. Suddenly, Western games, PCs, and publishing tools were available. Studios like LK Avalon in Rzeszów, Mirage in Warsaw, and Metropolis Software started making actual commercial titles. The scene still felt small, but ambition was growing.

Early titles

Some early titles still get talked about. Franko: The Crazy Revenge (1994) was raw and aggressive, a beat-’em-up that felt ripped from the streets of post-communist Poland. Fire Fight (1996), developed in cooperation with Electronic Arts, showed what was possible when local talent met global resources.

And then came Gorky 17 (1999). Developed by Metropolis Software, it mixed tactical gameplay with a strange horror vibe and made it onto store shelves around the world. It was moody, weird, and nothing like what most Western devs were making. It put designer Adrian Chmielarz on the map. But behind the scenes, something even more ambitious was being quietly shelved: a prototype of The Witcher.

The Witcher almost didn’t happen

Metropolis actually started the first Witcher game in the late ’90s. But the project was dropped. Why? The team wanted to focus on finishing Gorky 17. They weren’t sure if global audiences would get a game steeped in Slavic mythology. Too niche, maybe.

It was the CD Projekt that brought it back. Founded by two high school friends in Warsaw, CD Projekt started as a distributor, selling pirated and later licensed games out of backpacks and booths at the legendary market. By 2002, they had the rights to Sapkowski’s books and a small dev team ready to try again.

The Witcher: Poland levels up

Geralt of Rivia, the lead in The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, turned into a pop culture icon and a symbol of Poland’s game industry.

But before all the hype started…

When The Witcher finally launched in 2007, it wasn’t perfect. The combat was clunky, the engine was borrowed, and the voice acting was…inconsistent.

Still, something about it clicked. It had its own voice. It wasn’t trying to copy Western RPGs, instead, it embraced its Slavic roots, and players picked up on that right away.

By the time The Witcher 2 hit in 2011, CD Projekt RED had grown up. The game looked stunning, told a mature story, and played well.

But it was The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt in 2015 that changed the game entirely. Not just for CDPR, but for Poland. It became a national symbol.

Geralt and the global stage

The Witcher 3 sold millions within weeks. It won over 200 Game of the Year awards. Obama joked about it in a speech. The world saw a modern, creative industry instead of a “gray land of vodka and carts.”

And while CDPR soaked up praise, another Polish hit was right behind it. Techland’s Dying Light, developed in Wrocław, became one of the best-selling games of 2015. Parkour and zombies in a sunlit, deadly city. It scratched a different itch, and it proved that The Witcher wasn’t a one-off.

Polish studios and their flagship titles

The Witcher 3 wasn’t just a win for CD Projekt. It put the whole Polish game industry on the map. After its success, more people around the world started paying attention to what studios in Warsaw, Wrocław, or Kraków were making.

Techland had already made some noise with Call of Juarez in 2006 and Dead Island in 2011. Both games found their fans, and Dead Island sold really well. But Dying Light in 2015 was a big step up. It mixed parkour with zombie survival in a way that felt fresh and fun to play. It became one of the top-selling games that year and helped Techland go global.

Today, CD Projekt and Techland are Poland’s biggest game studios, each with major projects underway.

Other teams helped shape Poland’s reputation too.

11 bit studios from Warsaw went in a different direction with This War of Mine. It focused on civilians trying to survive during war. The game was serious, emotional, and didn’t feel like a typical strategy title. It won awards, sold well, and proved that Polish developers could make meaningful games.

People Can Fly made a name for themselves with Painkiller in 2004, a fast-paced shooter that built a strong following. Later, they worked on Bulletstorm and helped develop parts of the Gears of War series. They stuck with what they knew best, which is action that feels intense and fast.

In Kraków, Bloober Team focused on psychological horror. Their games like Layers of Fear and Observer leaned more into mood and tension than cheap scares. Their work got noticed around the world, and eventually Konami asked them to handle the Silent Hill 2 remake.

Flying Wild Hog, based in Warsaw, brought back Shadow Warrior with over-the-top humor and fast combat. It was loud and ridiculous , all in a good way. Then there’s SUPERHOT, a small project from a game jam that blew up. Its simple idea, time only moves when you move, turned it into a global hit without needing cutscenes or big budgets.

Cyberpunk, setbacks, and recovery

Then came Cyberpunk 2077. The hype was massive. Evan Keanu Reeves was involved. Unfortunately, the launch turned out to be a big mess. Bugs, crashes, refunds. It was rough, especially for fans who saw CDPR as the standard. But again, the devs stuck with it. Updates, expansions, and time helped. Eventually, it became what people hoped for. We got a vibrant, detailed future city and a story with characters you actually get attached to along the way.

What matters is that CD Projekt didn’t vanish. They’re still leading the charge, with a new Witcher saga in development and more Cyberpunk content on the way.

At the same time Techland’s working on a fantasy RPG. And every year, new Polish games keep showing up on Steam’s bestseller lists.

I really like some of the newer Polish games too. Frostpunk 1 and 2 were great: the mix of survival, leadership, and bleak choices stuck with me for days. It’s a brutal city builder where you try to keep your people alive in a frozen world, and every decision feels heavy.

Then there’s The Alters, which grabbed me the moment I saw the trailer. A sci‑fi survival game where you create alternate versions of yourself to survive. It’s strange, personal, and really captivating. Both come from 11 bit studios, and they clearly know how to make thoughtful games that stay with you.

Another one worth watching is Cronos: The New Dawn by Bloober Team. It’s a horror survival game set in Nowa Huta, a district of Kraków with real history and character. I love that they’re making something so rooted in place and identity.

Indies, school assignments, and what’s next

This War of Mine goes beyond entertainment. Developed in Warsaw, it’s now part of Poland’s high school curriculum. A game about surviving war as a civilian, studied alongside classic literature.

Indies like World War 3, Ghostrunner, and RUINER keep proving that you don’t need a massive team to make something memorable. With hundreds of studios across the country, Poland’s dev scene feels more like a movement than an industry.

Why does it work? Some say it’s because Polish teams stayed independent. Others point to the weird mix of Western tech and Eastern grit. Whatever it is, it seems to be working.